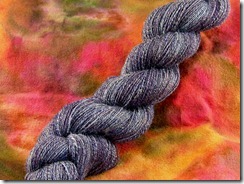

I am addicted to spinning lace yarn right now. I don’t know why. I’ve always been attracted to tiny crafts- I used to make little tiny sculptures from polymer clay. Before that, I would “miniaturize” anything I learned, like “god’s eyes” (I think I was about 8 when I learned that one). Once I got the hang of making one with popsicle sticks and worsted yarn, I started making them with toothpicks and embroidery floss. So I guess it was really just a matter of time before I found the tiny singles of laceweight. Before I left for Sock Summit, I finished up this pretty skein.

It’s spun from a 70% merino/30% silk blend that I bought a few years back, one of my first fiber purchases!

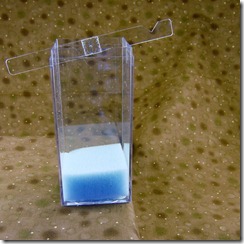

I don’t knit much lace, though, so I offered this skein to a friend who loves purple. Since I wanted to know how much I was giving her, I pulled out my McMorran balance. A McMorran balance is a nice, inexpensive little piece of equipment made from, basically, an acrylic box with some slots in it and an acrylic arm that wobbles. The magic is in the calibration. It’s calibrated to measure 1/100th of a pound. (Metric versions can be purchased if you’re not down with the inches and ounces.) Here’s what I did to measure my handspun (using some green Cascade 220 as the yarn, because lace yarn doesn’t show up well in photos):

Here’s the McMorran balance sitting on the edge of a book. You’ll see why it’s on a book shortly. See how the notched part of the arm is tilted up? That means the weight of the notched end is lighter than the solid end. Let’s add some yarn!

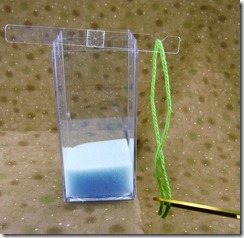

Cut off a 6-10" piece of the yarn you’re measuring. The thinner/lighter the yarn, the longer the piece you’ll need (laceweight might need a much longer piece, or several pieces). This piece is much heavier than the solid end of the arm. You can see that the ends of the yarn are below the bottom of the balance- that’s why it’s a good idea to place the scale at the edge of a table, so that the yarn can hang freely.

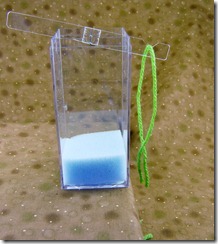

Cut off a little bit of the yarn, then let the scale settle back. Is it balanced (is the arm horizontal/not tilted)? If not, trim off another little bit. The key here is to trim off just a tiny bit each time. You can always cut more off, but it’s not easy to fix if you overshoot!

When the arm is horizontal, remove the piece of yarn and measure it with a ruler. Don’t stretch it out so it’s taut, but you want it to be straight. Let’s say this piece is 6” long. Now for a little math:

Multiply the length of yarn by 100. (6 inches x 100 = 600)

The resulting number is your “yards per pound” or ypp. (600 ypp)

Chances are good that you don’t have a full pound of yarn, though! Divide the number above by 16 (the number of ounces in a pound) to get the “yards per ounce” or ypo. (600 ypp/16 oz = 37.5 ypo)

Now weigh your skein. Multiply the weight of your skein by the ypo. (2.3 oz x 37.5 ypo= 86.25 yards)

The final number is how many yards are in your skein. (86.25 yards)

The instructions are the same for a metric version, but the math at the end is a little different. I haven’t actually found the calculation online anywhere, but the balances come with the formula.

So, in the end, it turns out that I have about 400 yards of my handspun laceweight. Not bad!